Customer loyalty campaigns abound: providing special offers and recognition to reward loyalty is an important part of the marketing toolkit. Figuring out whether a campaign is effective or not can be complicated - and a phenomenon I call ‘survival of the most engaged’ can often hide what’s really going on.

So what is this phenomenon and how do we avoid it?

Survival of the most engaged

The easiest way to understand this is with an example.

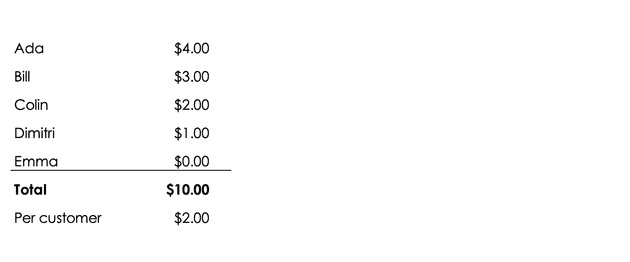

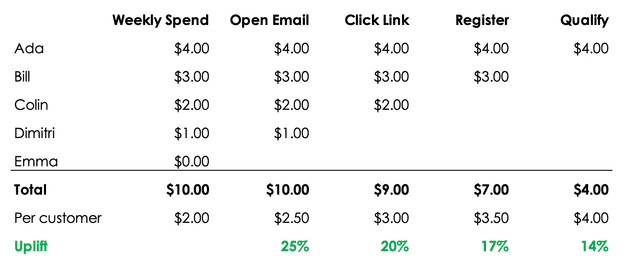

A company has 5 customers. Ada spends $4 a week on the company’s products. Bill spends $3, Colin $2, Dimitri $1 and Emma $0. Total spend is $10 and the average spend is $2 per customer.

The company targets all 5 customers for a loyalty promotion. The customers are sent an email with details of the promotion.

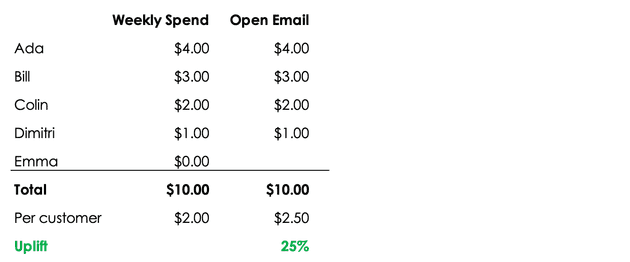

When Emma receives the email she deletes it without opening. She doesn’t view herself as a customer because she doesn’t buy any products from the company any more. The other 4 customers open the email.

If we track the campaign performance at this point, the spend of customers that opened the email is $10 and - because only 4 customers opened the email - the average spend has gone up. It’s now $2.50. So our campaign looks like it’s off to a great start - average spend is already up 25%.

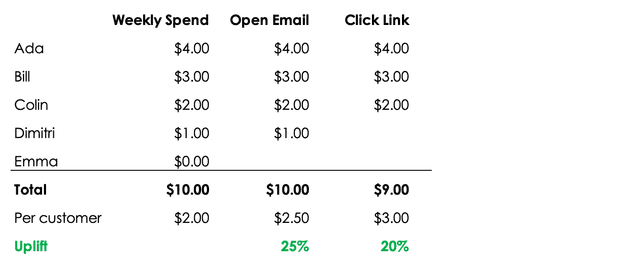

Dimitri has opened the email but isn’t interested in the offer so he deletes it. Ada, Bill and Colin go ahead and click the link to the registration page.

Now we look at our campaign performance: customers who click represent $9 of sales and have an average spend of $3 per customer. So it looks like another 20% improvement in average spend.

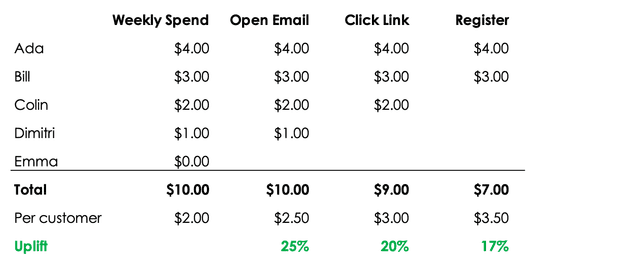

Colin takes a look at the registration website and - as an average spender - isn’t that bothered about signing-up. Ada and Bill both register and average spend jumps by 17% to $3.50.

Ada qualifies for the loyalty benefit because of her existing higher spend.

The average spend of customers who qualify - just Ada - is $4, 14% higher than those that registered for the campaign, and 100% more than the average spend of the customer base targeted for the promotion.

The Most Engaged… are the most engaged

With this example it’s simple to see what’s going on. The doubling of average spend from $2 to $4 per customer has happened without any change in underlying customer behaviour.

The customers who spend the most have self-selected into the campaign and jumped-through the campaign hoops to qualify for the loyalty promotion. Customer who are less engaged don’t bother. It’s this self-selection in or out of the campaign that drives the change in average spend.

The most engaged customers ‘survive’ all the steps the company forces them through. Others fall by the wayside by not opening the email, not clicking on the register link, not registering or not having enough qualifying spend.

Addressing the problem: Cohort Analysis

Just as it’s simple to see the problem when set out like this, it’s also easy to see the solution. We need to track spend at a customer level. Specifically, we need to look at pre-promotion and post-promotion customer-level spend.

If we did this for the example above we’d see that Ada’s spend didn’t changed as a result of the promotion.

More generally we need to look at customer cohorts and define the cohort based on the outcomes - such as all the customers that qualified for the promotion - and see how this group’s spend changes over time.

Most critical - and most difficult to influence - is the post-promotion spend. Customers who change their behaviour during a promotion is good; customers who maintain their changed behaviour after the promotion is better.